Many explanations and block explorers encourage the idea that once a transaction is sent, the whole network instantly knows about it. This guide unpacks why decentralized nodes never share a single, perfectly synchronized view of pending transactions. A mempool is the local data structure where a node holds valid, unconfirmed transactions it currently knows about. We will look at how transactions move between nodes via gossip, why mempools are local and policy-driven, and why nodes disagree about which transactions exist at a given moment. We will not walk through wallet interfaces, trading workflows, or protocol-specific fee rules. The focus is the network-level mechanism: how transactions propagate, why propagation is slow and lossy, and what mempool visibility can and cannot tell you about eventual inclusion.

The misconception: a single shared mempool

- The mempool is not a single global database; it is a separate local data structure on each node.

- Broadcast is not instant delivery; it is the start of a best-effort gossip process across limited peers.

- Network visibility is not uniform; different nodes legitimately see different pending transactions at the same time.

- Mempool presence is not a promise of inclusion; it only means some node is currently storing the transaction.

- Explorer output is not ground truth; it reflects the mempool view of specific nodes, not the entire network.

What a mempool actually is

- Local: each node has its own mempool, populated only with transactions it has received and accepted.

- Ephemeral: mempool contents change constantly as transactions arrive, are included in blocks, or are evicted.

- Policy-driven: nodes apply local rules for minimum fees, size limits, and replacement, which shape mempool contents.

- Best-effort: nodes attempt to relay and store useful transactions but are not required to hold or forward everything.

- Outside consensus: mempool state is not agreed upon by the network and is not recorded on-chain.

Local views and partial knowledge

- Connectivity: nodes have different peers, so some receive a transaction along short paths while others never see it.

- Timing: even with identical peers, message arrival order and network latency create short-term differences in mempool contents.

- Fee thresholds: nodes may reject or evict transactions below a local minimum fee rate, while others still keep them.

- Eviction: when mempools are full, nodes drop lower-priority transactions, leading to divergent sets.

- Filtering: nodes may apply additional policy filters (e.g., size, complexity, or risk rules) that cause them to ignore certain transactions.

Vignette: Same transaction, different local reality

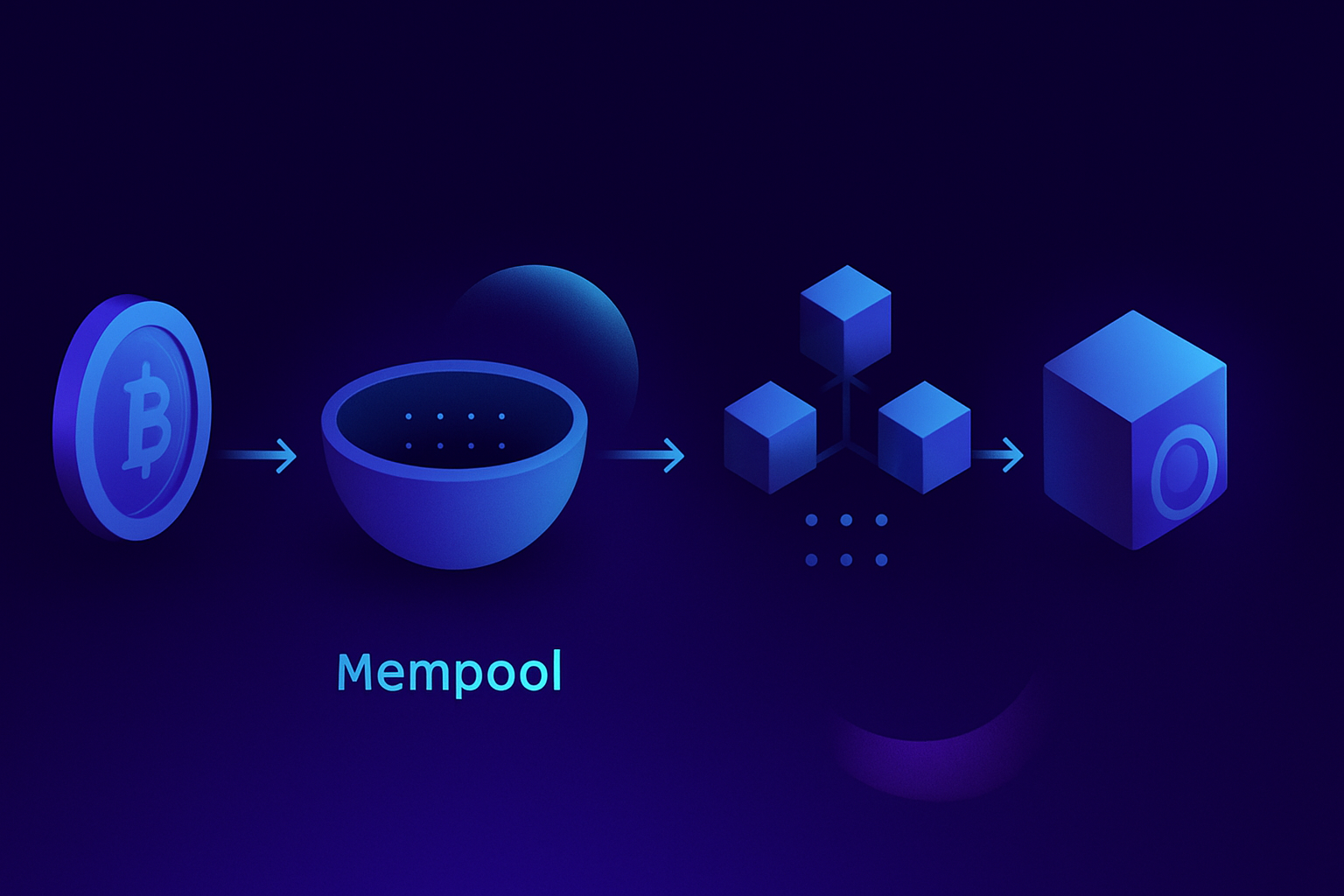

Gossip and transaction propagation

- A transaction is created and sent to one or a few initial nodes in the network.

- An entry node performs basic validation and, if acceptable, inserts the transaction into its local mempool.

- That node marks the transaction as new and schedules announcements or relays to a subset of its peers.

- Receiving peers validate the transaction independently and, if they accept it, add it to their own mempools.

- Each of those peers then repeats the process, gradually spreading the transaction across their respective peer sets.

- At every hop, local policies, rate limits, and temporary issues can slow, filter, or stop further propagation.

Why propagation is slow, uneven, and lossy

- Geography: long-distance network links add latency, so distant nodes learn about a transaction later.

- Peer selection: each node has a limited, changing peer set, so some parts of the network are only weakly connected.

- Filtering: nodes may drop low-fee or suspicious transactions early, preventing them from spreading widely.

- Back-pressure: when bandwidth or CPU is constrained, nodes throttle or defer transaction relays.

- Temporary outages: node restarts, peer disconnects, and routing issues interrupt propagation paths.

Why transactions can disappear

- Eviction by fee or age: when space is scarce, nodes drop older or lower-fee transactions to admit new ones.

- Validation failure: malformed, double-spending, or otherwise invalid transactions are rejected and never stored.

- Replacement: a newer transaction spending the same inputs with higher effective fee can displace the older one.

- Node restart: unless persisted, mempool contents are cleared when a node stops and restarts.

- Incomplete propagation: some nodes never receive a transaction due to network issues or upstream filtering.

Vignette: The vanishing low-fee transaction

Visibility vs inclusion: what mempools do not guarantee

- Broadcast: the transaction is handed to one or a few nodes to start gossip; this is an action, not proof of network-wide delivery.

- Received: a specific node has accepted the transaction into its mempool; this is observable only from that node’s perspective.

- Seen by producers: block-producing nodes have the transaction in their mempools; this is inferred, not directly observable in most systems.

- Included: the transaction appears in a valid block on the canonical chain; this is the first durable, consensus-level record.

What mempools guarantee — and what they don’t

Key facts

UX uncertainty as a system property

Pro Tip:Treat mempool data as a hint about current network conditions, not as a commitment about inclusion or timing. Short-term disagreement between explorers, nodes, and services is normal because each one is sampling a different local view.

Where mempools fit in the transaction lifecycle

- Transaction creation: data is constructed and sent to one or more entry nodes (mempool not yet involved).

- Initial acceptance: an entry node validates the transaction and, if acceptable, adds it to its local mempool.

- Propagation: the transaction gossips across peers, entering and leaving various nodes’ mempools.

- Selection: block-producing nodes consider transactions from their local mempools when assembling candidate blocks.

- Confirmation or abandonment: once included in a block, the transaction leaves mempools; otherwise it may be evicted or forgotten.

The mempool mental model

- Mempool contents are local, temporary views of unconfirmed transactions, not shared global state.

- Gossip is best-effort: broadcast starts propagation but does not ensure universal delivery.

- Transactions can be evicted, replaced, or forgotten from mempools without ever reaching the chain.

- Inclusion happens in block construction, using the mempools of specific producers at specific times.

- Mempool visibility is a hint about possibilities, not a guarantee about outcomes.