If you follow crypto news, you have probably seen headlines about a blockchain "forking," new coins suddenly appearing, or exchanges pausing deposits. For many users, it feels like the rules change overnight and it is not clear whether their existing coins are safe. In this guide, you will learn what a blockchain fork actually is, and how it relates to the shared history that all nodes agree on. We will break down soft forks versus hard forks, why they happen, and what typical effects they have on balances, wallets, and trading. By the end, you will know when you can mostly ignore a fork, when you should pay close attention, and which simple steps help you stay safe and avoid unnecessary stress during these events.

Quick Summary: Forks in One Glance

Summary

- A fork happens when some nodes follow one set of rules and others follow a different set, creating competing versions of the chain.

- A soft fork tightens rules but stays compatible, so old nodes still accept new blocks and the chain usually does not permanently split.

- A hard fork changes rules in a non-compatible way, so the network can permanently split into two chains and two coins.

- Users rarely need to act during soft forks beyond keeping wallets updated and following project announcements.

- During hard forks, users should check which chain their exchange and wallets support, and whether they will credit any new coins.

- Forks often bring short-term confusion and volatility but can also introduce important upgrades or new project directions.

Core Concept: What Is a Fork in a Blockchain?

- Network latency or delays cause two miners or validators to produce valid blocks at almost the same time, briefly creating competing branches.

- Planned protocol upgrades introduce new features or performance improvements that require changing the rules nodes follow.

- Bug fixes or security patches tighten what counts as a valid transaction or block to protect the network from known issues.

- Community disagreements about fees, block size, or monetary policy lead different groups to support different sets of rules.

- Emergency responses to hacks or critical exploits can trigger forks that attempt to reverse or isolate malicious transactions.

- Experimental projects sometimes fork an existing chain to test new economic models or governance systems without starting from zero.

How Forks Actually Happen on a Network Level

- Developers or community members propose a rule change, such as a new feature, bug fix, or policy adjustment, and discuss it publicly.

- Once agreed, they release updated node software that encodes the new consensus rules and often includes an activation block height or time.

- Node operators, miners, and validators decide whether to install the new software, leading to a mix of upgraded and non-upgraded nodes on the network.

- When the activation point is reached, upgraded nodes start enforcing the new rules, while old nodes continue enforcing the previous rules.

- If blocks are created that satisfy the new rules but violate the old rules, the two groups of nodes disagree and begin following different chains.

- Over time, the network either reconverges on one chain, as in many soft forks, or remains split into two ongoing chains, as in contentious hard forks.

Soft Forks: Backward-Compatible Rule Changes

- Soft forks usually restrict what is allowed, such as tightening script rules or limiting block contents, so that all new blocks still look valid to old nodes.

- Because old nodes accept blocks from upgraded miners, the chain does not normally split into two long-lived versions.

- Bitcoin’s SegWit upgrade in 2017 was a soft fork that changed how signatures were stored, improving capacity and fixing transaction malleability while keeping old nodes compatible.

- Most users experienced SegWit simply as faster, cheaper transactions once their wallets and exchanges adopted the new format, without needing to claim any new coins.

- Soft forks are often used for incremental improvements where the community mostly agrees on the direction and wants to avoid a disruptive split.

Pro Tip:Soft forks rarely create "free coins" or force you to pick a side. As long as your funds are in a secure, well-maintained wallet, simply updating your software and following official project announcements is usually enough.

Hard Forks: Non-Compatible Splits and New Chains

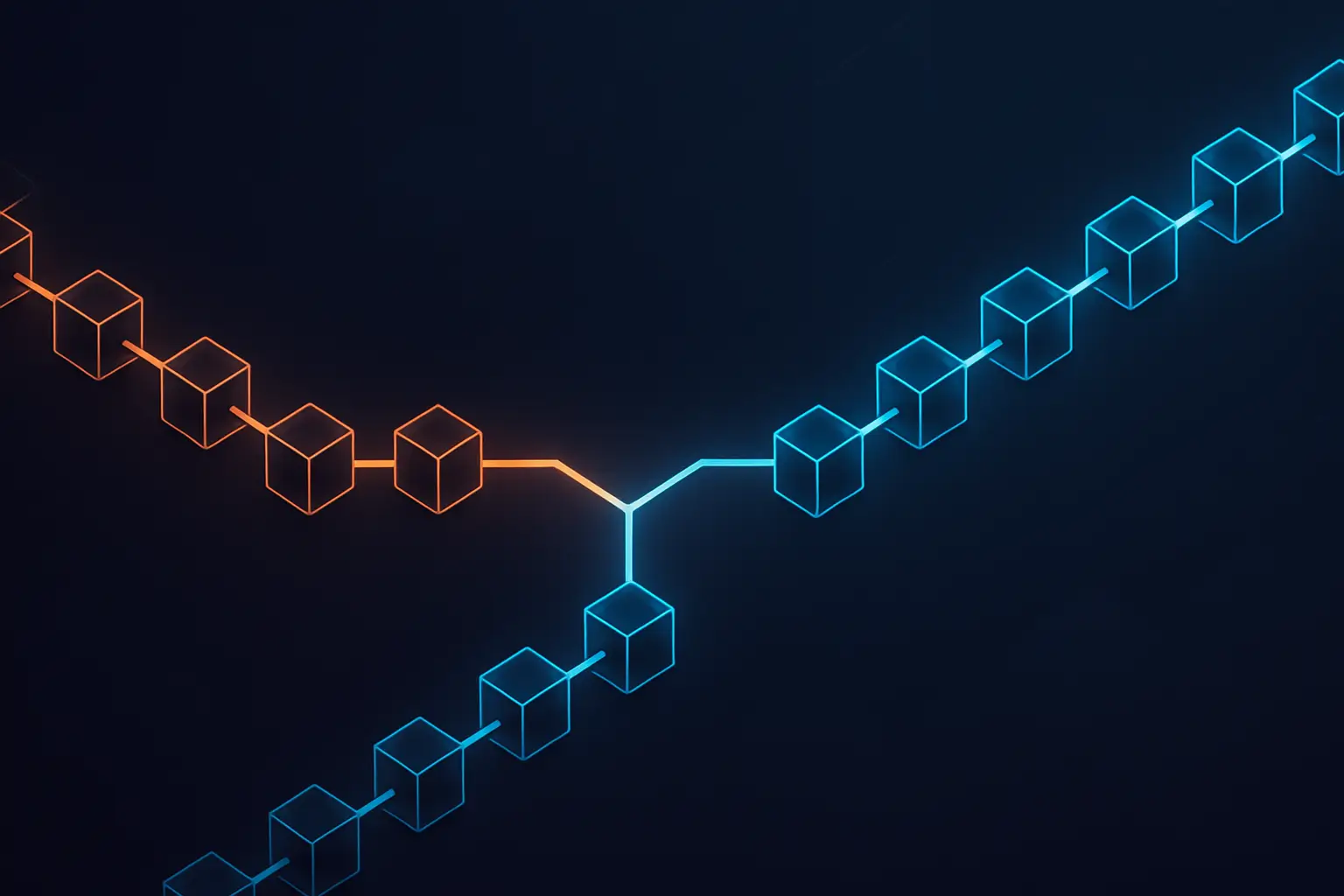

- A contentious hard fork can create two ongoing chains, each with its own community, development roadmap, and branding.

- At the fork block, balances are often duplicated, so holders may end up with coins on both chains, assuming their wallets and exchanges support them.

- Projects typically rebrand one or both chains with different names and tickers to distinguish them in markets and on exchanges.

- Exchanges may pause deposits and withdrawals during the fork, then later decide which chain to list, or list both with separate tickers.

- Wallet providers must choose which chain to support by default and may need to add special tools for users to access coins on the other chain.

- News, social media, and price volatility around the event can create short-term confusion and opportunities for both profit and scams.

Soft Fork vs Hard Fork: Key Differences for Users

Key facts

Historical Highlights: Famous Blockchain Forks

Forks are not rare glitches; they are key turning points in the history of major blockchains. When communities hit disagreements or crises, forking the chain can be the way they choose a direction. Some forks, like Bitcoin’s SegWit upgrade, quietly improve the system without drama. Others, like the split between Ethereum and Ethereum Classic, reflect deep philosophical divides about immutability, governance, and how to respond to hacks.

Key Points

- 2013–2016: Early Bitcoin soft forks gradually tighten rules and add features, showing that backward-compatible upgrades are possible without splitting the chain.

- 2016: After the DAO hack on Ethereum, a controversial hard fork reverses the hack on the main chain (ETH), while dissenters keep the original chain as Ethereum Classic (ETC).

- 2017: The Bitcoin community debates scaling; one path implements the SegWit soft fork, while another group launches a hard fork that becomes Bitcoin Cash (BCH) with larger blocks.

- 2017–2018: Multiple Bitcoin Cash hard forks occur, including the split into BCH and BSV, illustrating how repeated disagreements can fragment a community and its liquidity.

- 2021: Bitcoin’s Taproot soft fork activates, improving privacy and scripting capabilities with broad consensus and minimal user disruption.

- Ongoing: Many smaller projects use planned hard forks as scheduled upgrade points, coordinating the whole community to move to a new version without leaving a competing chain behind.

Case Study / Story

Why Forks Matter: Real-World Purposes and Outcomes

Forks can look like pure drama from the outside, but they are also powerful tools for shaping a blockchain’s future. In open-source systems, anyone can copy code or propose new rules, and forks are how those ideas are tested in the real world. Developers use forks to ship upgrades, fix bugs, or respond to emergencies. Communities use them to express different visions for fees, privacy, or monetary policy. Investors and users feel the impact in the form of new features, changed incentives, or entirely new coins competing for attention.

Use Cases

- Implementing scaling upgrades that change how data is stored or validated, allowing more transactions per block or lower fees.

- Adding new features such as improved scripting, smart contract capabilities, or privacy enhancements that require consensus rule changes.

- Responding to hacks or critical bugs by deciding whether to reverse specific transactions or leave the chain untouched, sometimes leading to split communities.

- Resolving governance disputes over block size, fee markets, or monetary policy by allowing different factions to pursue their preferred rules on separate chains.

- Adjusting protocol behavior to better align with regulatory expectations or compliance requirements, such as blacklisting certain addresses or tightening KYC-related rules at protocol edges.

- Launching experimental economic models, like different inflation schedules, staking rewards, or treasury systems, without abandoning the existing user base entirely.

- Scheduling predictable, non-contentious hard forks as upgrade milestones so the whole community can coordinate on major version changes.

Practical Guide: What Should You Do When a Fork Is Coming?

- Read the project’s official announcements and a couple of neutral explainers to understand whether the fork is soft or hard, and what the goals are.

- Check your main exchanges and wallets for statements about which chain they will support and whether they plan to credit any forked coins.

- Beware of scams that ask you to enter your seed phrase or private key to "claim" forked coins; only use tools recommended by reputable wallet providers.

Risks and Security Concerns Around Forks

Primary Risk Factors

Forks create short periods where the usual assumptions about a blockchain can break down. Two chains may share the same history up to a point, tools may not fully support both, and scammers know that users are distracted. During these windows, technical issues like replay attacks or chain reorganizations can interact with human mistakes, such as sending coins to unsupported chains or trusting fake claim tools. Understanding the main risk types helps you recognize when to slow down and double-check your actions.