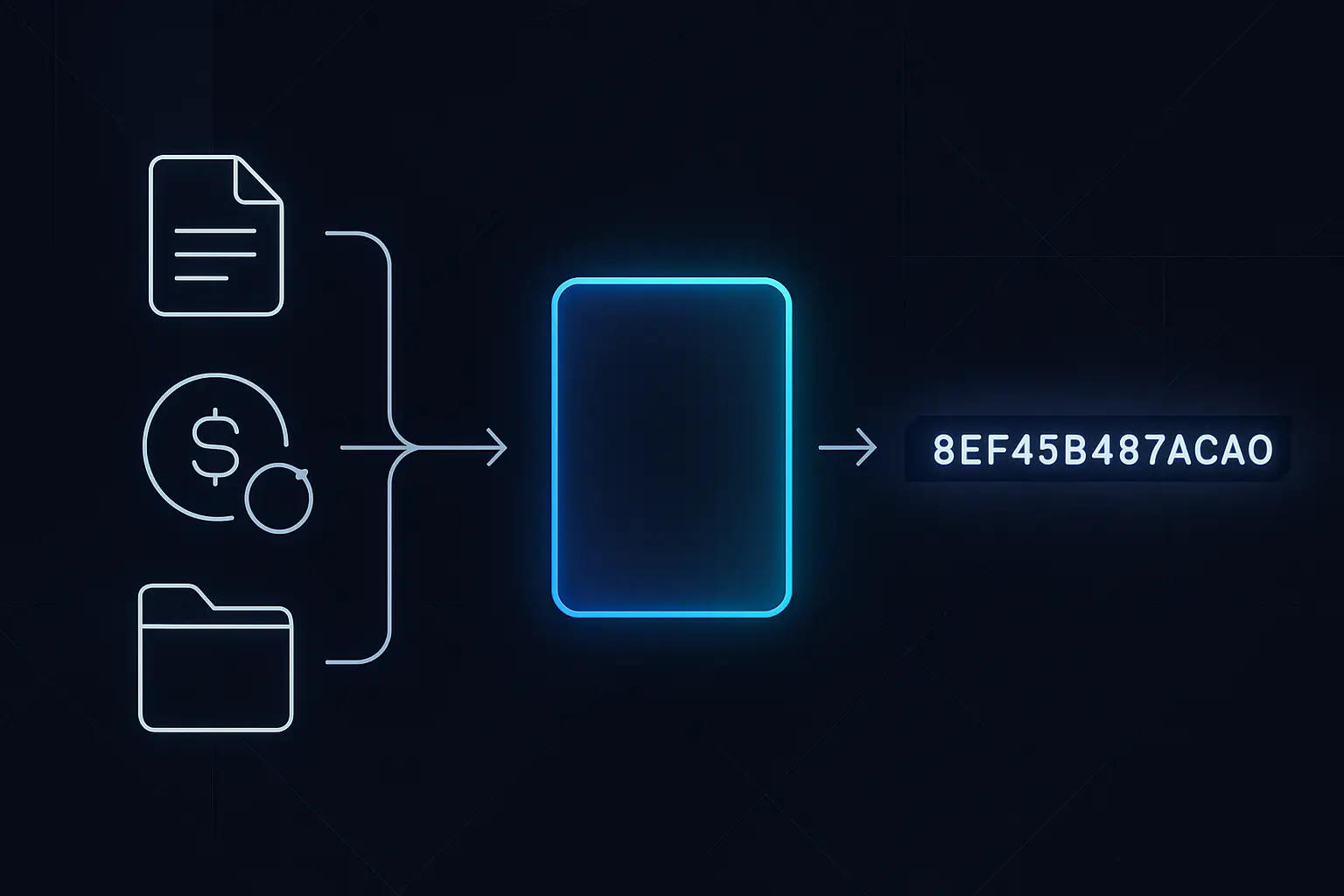

When people talk about blockchains being "immutable" or "tamper‑proof," they are really talking about hashing. A hash is a short code, created by a special formula, that uniquely represents a piece of data like a transaction, file, or whole block. It’s often compared to a digital fingerprint: easy to create from the original data, but impossible to turn back into that data. If even one character of the input changes, the fingerprint (hash) changes completely, making any alteration obvious. Hashing is what lets thousands of blockchain nodes agree on the same history without a central authority. It links blocks together, powers proof‑of‑work mining, and helps users verify data integrity without seeing all the underlying information. In this guide we’ll focus on the ideas, not the math. You’ll see how hashing works in practice, especially in systems like Bitcoin, so you can explain it clearly and spot misleading or scammy claims that misuse these terms.

Quick Take: Hashing in Blockchain at a Glance

Summary

- Turns any input (transaction, file, message) into a fixed‑length hash code that uniquely represents that data.

- Is one‑way: you can easily go from data to hash, but you cannot recover the original data from the hash.

- Is extremely sensitive: even a tiny change in the input produces a totally different hash output.

- Links blocks together by storing each block’s hash inside the next block, making tampering obvious and costly.

- Powers proof‑of‑work mining, where miners race to find a hash that meets a difficulty target.

- Lets users and nodes verify data integrity ("this hasn’t changed") without needing to see or trust all the underlying data.

Hashing Basics: The Idea Without the Math

- Produces a fixed‑size output no matter how large or small the input data is.

- Is deterministic: the same input will always give exactly the same hash output.

- Is effectively one‑way: you cannot reconstruct the original data from the hash in any practical amount of time.

- Shows avalanche behavior: changing even one bit of input completely changes the resulting hash.

- Is designed to be collision‑resistant, meaning it is extremely hard to find two different inputs that produce the same hash.

Hashing Beyond Crypto: Everyday Uses

- Verifying downloaded files by comparing their hash to a trusted value posted by the software publisher.

- Storing password hashes instead of raw passwords so a database leak reveals only scrambled values.

- Detecting duplicate photos, videos, or documents by comparing their hashes instead of their full contents.

- Checking data integrity in backups or cloud storage by re‑hashing files and comparing them to earlier hashes.

- Powering content‑addressable storage systems, where files are retrieved using their hash instead of a human‑chosen name.

How Hashing Secures Blockchains

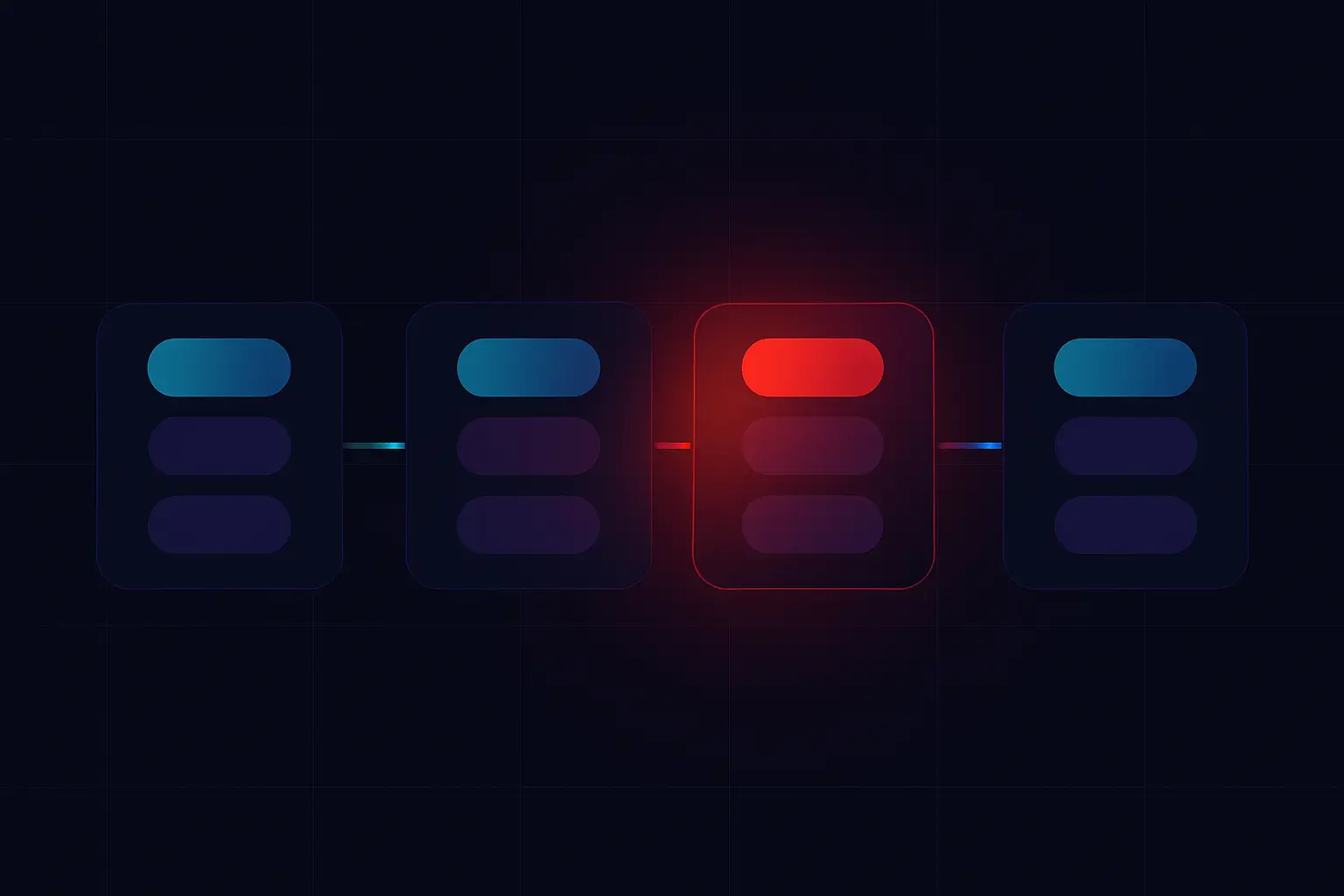

- Makes the chain effectively immutable: altering one block breaks all later hashes, exposing tampering.

- Allows nodes to quickly verify that a received block matches the expected block hash without re‑downloading everything.

- Enables light clients (SPV wallets) to verify transactions using block and Merkle tree hashes instead of the full blockchain.

- Helps thousands of nodes stay in sync, since they can compare hashes to agree on the same chain history efficiently.

Pro Tip:When you look at a block explorer, the long strings you see labeled as "block hash" or "transaction hash" are these digital fingerprints in action. By understanding that they uniquely summarize the data, you can confidently track your own transactions, confirm which block they’re in, and spot when someone is showing you a fake screenshot that doesn’t match the real chain.

Common Hash Functions in Crypto (SHA-256, Keccak, and More)

Key facts

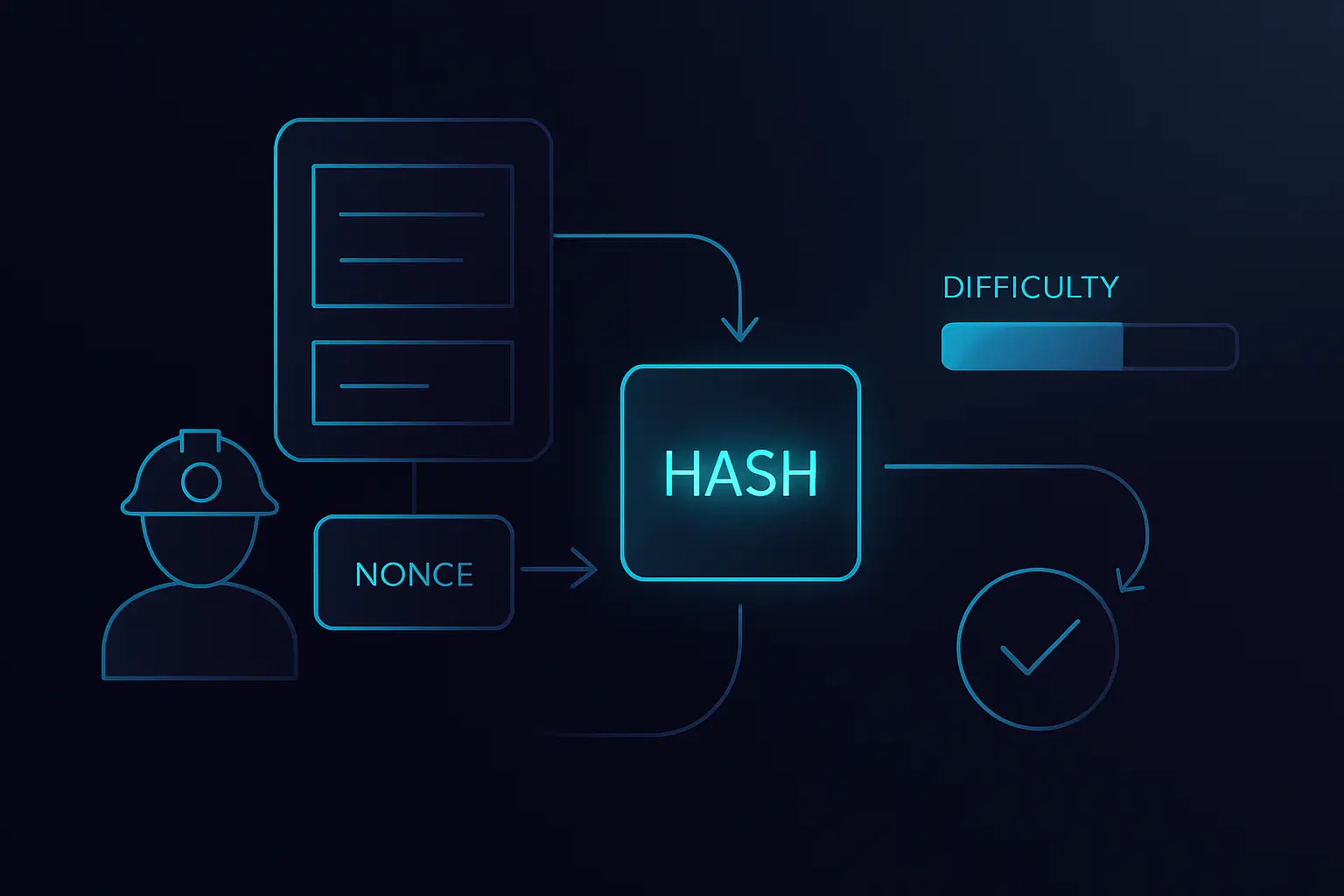

Hashing and Proof of Work: Mining in One Picture

- Cheating is expensive because an attacker would need to redo enormous amounts of hashing work to rewrite history and still meet the difficulty target.

- The network regularly adjusts difficulty so that, on average, blocks are found at a predictable rate even as total mining power changes.

- Verification is cheap: other nodes only need to hash the block header once and check that the result meets the difficulty rule.

- This asymmetry—hard to find a valid hash, easy to verify it—is what makes proof of work a powerful anti‑tampering mechanism.

Case Study / Story

Risks, Limits, and Security Considerations of Hashing

Primary Risk Factors

Hashing is powerful, but it is not magic security dust. A hash only proves that data hasn’t changed; it does not hide the data or prove who created it. Many breaches happen because developers misuse hashing. For example, storing passwords as a simple SHA‑256 hash without a salt or slow password‑hashing function makes them easy to crack if the database leaks. Using broken algorithms like MD5 or SHA‑1 for new systems is also risky because they have known weaknesses. Users can also misinterpret what they see. A transaction hash is not a password or private key, and sharing it doesn’t give anyone control over your funds. Understanding these limits helps you spot bad security practices and avoid projects that misuse cryptographic buzzwords.

Primary Risk Factors

Security Best Practices

Hashing vs Encryption vs Digital Signatures

Pro Tip:A new user once copied their transaction hash into a "support" chat after a scammer asked for their "key" to fix a stuck payment. Luckily, the hash alone didn’t give access, but it showed how easily terms get mixed up. Knowing the difference between hashes, keys, and signatures helps you spot these tricks early.

Practical Use Cases of Hashing in Blockchain

Even if you never write a line of smart contract code, you interact with hashes whenever you use crypto. They quietly label and protect almost every piece of data on a blockchain. From transaction IDs to NFT metadata, hashes let wallets, explorers, and dApps agree on exactly which data they’re talking about. Knowing this helps you understand what you’re seeing on‑screen and why it’s hard to fake.

Use Cases

- Creating transaction hashes (TXIDs) that uniquely identify each on‑chain transaction you send or receive.

- Labeling blocks with block hashes, which summarize all the data in a block and link it to the previous one.

- Building Merkle trees, where many transaction hashes are combined into a single Merkle root stored in the block header.

- Protecting NFT metadata by hashing artwork files or JSON metadata so marketplaces can detect if content has been altered.

- Supporting cross‑chain bridges and layer‑2 systems that post compact state hashes to a main chain as proofs of off‑chain activity.

- Enabling on‑chain verification of off‑chain data (like documents or datasets) by comparing their current hash to a hash stored in a smart contract.

FAQ: Hashing in Blockchain

Key Takeaways: Understanding Hashing Without the Math

May Be Suitable For

- Crypto investors who want to judge technical claims without deep math knowledge

- Web and app developers integrating wallets, NFTs, or payments into their products

- NFT creators and digital artists who care about proving originality and file integrity

- Security-conscious users who want to understand what block explorers and wallets show them

May Not Be Suitable For

- Readers looking for formal cryptography proofs or detailed mathematical constructions

- People who need implementation-level guidance on writing their own hash functions

- Users only interested in trading prices with no interest in how blockchains work under the hood

Hashing is the quiet engine behind blockchain security. A hash function turns any amount of data into a fixed‑length digital fingerprint that is deterministic, one‑way, and extremely sensitive to change. By giving every block and transaction its own hash, and by linking blocks through previous block hashes, blockchains make tampering obvious and expensive. Proof‑of‑work systems add a lottery based on hashing, where it is hard to find a valid hash but easy for everyone else to verify it, enabling trustless consensus without a central authority. At the same time, hashing has clear limits: it does not encrypt data, it does not prove who sent a transaction by itself, and it can be weakened by bad algorithm choices or poor implementation. If you remember hashes as digital fingerprints for integrity, and combine that with an understanding of keys and signatures, you already have a strong mental model for exploring deeper topics in crypto.